The Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast—including the Haida, Tlingit, Coast Salish, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Kwakwaka’wakw—developed one of the most complex and stratified non-agricultural societies in human history. Their culture was defined by the staggering abundance of the ocean and the towering cedar forests.Pre-Contact PopulationEstimating numbers before European arrival is difficult, but scholars suggest the Pacific Coast was one of the most densely populated areas north of Mexico. * Estimated Population: Between 200,000 and 500,000 people lived along the coast from Alaska to the Columbia River. * Density: Because the salmon runs provided such a reliable, “storable” food source, these groups could live in permanent winter villages rather than wandering as nomads.

Social Structure and Property

Unlike many interior tribes where land was often communal, Coastal First Nations had a highly developed sense of private and lineage-based property.Methods of Keeping Property SeparatedResource ownership was not about “territory” in a vague sense, but about specific functional sites. A high-ranking family didn’t just own a forest; they owned the specific spot where a salmon trap was placed or a particular berry patch. * Boundary Markers: While they didn’t use fences, geographic landmarks (rivers, specific rocks, or mountain peaks) served as clear borders. *

Heraldry:

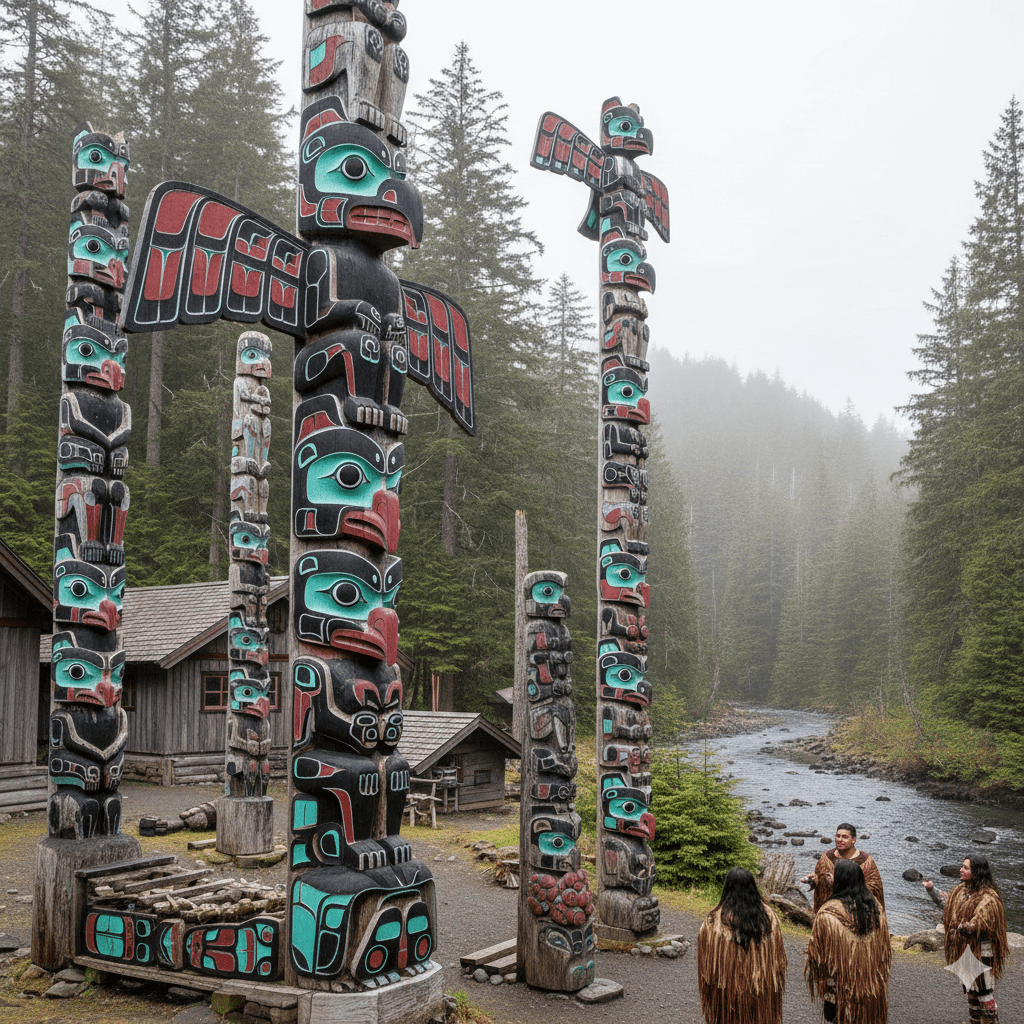

Totem poles and house front paintings acted as “deeds.” By displaying certain crests (like the Raven or Bear), a family publicly asserted their ancestral right to the resources of that area.

* Oral Histories:

At gatherings, “speakers” would recite the lineage and history of a family, effectively renewing their legal claim to their lands and waters in front of witnesses.

Traditions:

The PotlatchThe Potlatch was the heartbeat of coastal culture. It was a massive feast used to mark births, deaths, or the raising of a totem pole.

* Wealth through Giving:

In this culture, status wasn’t measured by how much you had, but by how much you gave away. A chief would give away blankets, copper shields, and food to guests from other tribes. * Legal Validation: By accepting the gifts, the guests were essentially “signing” a contract, acknowledging the host’s new rank or claim to property.Hostilities and WarfareLife on the coast wasn’t always peaceful. The same wealth that allowed for great art also fueled intense competition.

* Motivations:

Warfare was rarely about seizing large swaths of land. Instead, it was about revenge (blood feuds), the acquisition of slaves, and the capture of prestige items or specific resource sites.

* Fortifications:

Many villages were built on “defensive sites”—steep bluffs or small islands with palisades—to guard against midnight raids. * The War Canoe: These were the “battleships” of the coast. Carved from a single cedar log, some could hold 50 to 60 warriors. They allowed for high-speed, long-distance raids along the “Inside Passage.”

Art

There are the specific artistic styles of the different coastal groups, such as the distinction between Haida and Coast Salish formline art.

Distinction

To understand the distinction between these groups, it helps to look at their Formline art—the sophisticated mathematical and aesthetic system that defines Pacific Northwest visual culture. While they share similarities, the Haida and Coast Salish represent two very different ends of the artistic and social spectrum.

Haida Art:

The “Northern” Style

The Haida (along with the Tlingit and Tsimshian) developed what is often called the “Classic” Northern style.

It is characterized by bold, interconnected lines and a strict adherence to traditional rules. * The Formline: This is the primary black outline that defines the subject. It flows continuously, varying in thickness to create a sense of tension and fluid movement. * Ovoids and U-Shapes: Almost all Haida art is composed of these two shapes. The Ovoid (a rounded rectangle) usually represents joints, eyes, or heads, while U-shapes represent feathers, ears, or fins. * Symmetry and Complexity: Haida art is often “packed,” meaning every available inch of a box, pole, or mask is filled with secondary and tertiary figures. This reflected their highly stratified social hierarchy—everything had its place.Coast Salish Art: The “Southern” StyleThe Coast Salish (from the area around modern-day Vancouver and Victoria) practiced a style that was historically more minimalist and spiritually focused compared to the bold, heraldic art of the North. * Primary Shapes: Instead of the Ovoid, the Salish used the Trigon, Circle, and Crescent. These shapes were often carved “out” of the wood to create negative space, rather than being painted as bold outlines. * Human-Centric:

Classic style

Southern

While Northern art focused heavily on crest animals (Ravens, Eagles, Wolves), Coast Salish art frequently featured human figures, often representing ancestors or spirit helpers. * Visionary Purpose: Much of this art was created for private spiritual use or to adorn functional items like spindle whorls (used for weaving) and house posts, rather than the massive public totem poles found further north.

Comparison

Haida (Northern)

Coast Salish (Southern)

The Cedar:

The Foundation of Both:

Regardless of the style, the Western Red Cedar was the “Tree of Life” for both groups.

* The Wood:

Rot-resistant and straight-grained, it was split into planks for longhouses or hollowed out for canoes.

* The Bark:

Women would harvest the inner bark in the spring, which was then shredded and woven into water-tight hats, baskets, and even clothing.